For more than a century, Yemen’s Zaydi clans have been at war with local warlords, neighbouring states, and great powers, seeking an independent state along the Red Sea. Now, they’re showing their leverage by launching drone strikes against Israel and merchant ships transiting the sea. A few American bombs won’t make them change course.

New Delhi: ‘Everyone here has been so kind that I ought not to criticise the place,’ the newly-arrived young colonial civil servant wrote to his mother from the port city of Aden in the summer of 1962, ‘but it is suffocatingly colonial. I have been out to continual dinner, lunch and cocktail parties without having a single Arab invited to meet me. The food is generally appalling, and one has to put on evening trousers and shoes and a cummerbund to eat it; we even had to change clothes for a cocktail party.’

Yemen, 200,000 sq km of desert and farmland, did not at that time have a single local doctor, nor a modern school, a railway, or a factory.

Earlier this month, US President Donald Trump’s government resumed bombing that country, killing 31 people. ‘Hell will rain down on you’, Trump warned Ansar Allah, the de facto ruler of a large tract of territory in the country’s west, along the Red Sea. There have since been reports the United States is massing B-2 bombers at its Indian Ocean base in Diego, Gaza, in preparation for future strikes.

Ever since 2023, Ansar Allah, who you may have also heard of described as Houthi rebels or Zaidis, have been firing missiles at Israel and shipping transiting the Red Sea. Though some ships continue to transit the Red Sea and it’s a vital corridor for trade between Asia and Europe, others are taking the much longer route along the Horn of Africa. The war in the Red Sea has been overshadowed for days now by revelations that Trump cabinet members messaged each other with their war plans in a chat group to which, who knows why, they added a journalist.

❗️US ships now included in BAN on maritime shipping — Houthi leader Abdul-Malik al-Houthi

Missile and drone attacks to CONTINUE if American bombings don’t stop

Says escalation will be met with further escalation by Yemen's armed forces https://t.co/1wP16iKQeK pic.twitter.com/tQwbY8D5Cf

— RT (@RT_com) March 16, 2025

That story, as funny as it is, also tells us something quite dark though. Trump’s plans, such as they are, seem to consist of the idea that bombing Ansar Allah into submission will end the war or at least make it stop targeting Israel and Red Sea shipping. Fine, you might think that’s a plan.

Except that was also President Joe Biden’s plan. Following Ansar Allah’s attacks on shipping in 2023, the US and the UK had bombed Yemen and Israel followed up with attacks of its own. There was also before that Donald Trump’s plan in his first term.

And before that, it was President Barack Obama’s plan, who used drone warfare and airstrikes against Al-Qaeda in Yemen. The data shows that there have been hundreds of airstrikes since 2011 carried out by the US. And the problem is still, obviously, exactly where it was.

For the most part, Western shipping companies have said they intend to continue avoiding the Red Sea and routing traffic the longer way, despite Trump’s strikes. This week in the Print Explorer, I’ll be looking at why this conflict has raged for so long and how the world’s greatest power has failed to end it.

Also Read: Why ceasfire at key Pak-Afghan border crossing on Durand Line is unlikely to last long

The arrival of Empires

Think brutal desert punctuated by towns with incredible high-rise mud houses, built by the wealth of traders who sent frankincense and myrrh into the ancient world. Think lush green fields watered by the monsoon. Think the largest expanse of sand in the world with absolutely nothing on it. This geographical division of Yemen was also reflected in its power structures.

The northern side in the West was home of the Zaidi sect, led by their Imam, the religious and temporal leader who exercised power from at least the 10th century onwards. The south, more agricultural, was ruled by the sheikhs, the leaders of numerous tribal fiefdoms. And as for those grey eastern sands, well, nobody really ruled them at all.

For the most part, colonial powers had little interest in exercising control over this territory, except that is one small part of it. From the 16th century onwards, as both Turkey and Portugal expanded into the Indian Ocean, the port of Aden acquired strategic significance. The two empires, that is the Ottomans and the Portuguese, tried to stamp out piracy from the Red Sea, so that they alone were able to tax the lucrative trade between the Red Sea ports and India.

The next part of the story will be familiar to every Indian. European desire for coffee led the East India Company to begin operations in southern Arabia and they set up a trading port in 1618 at a small place called Mokha, a word I am sure you’ve heard of. Well, the coffee boom didn’t last long.

The rise of plantations elsewhere in the world relegated Yemen to economic obscurity again by the middle of the 18th century. Though Mokha is still there. For the British though, Yemen’s economic irrelevance mattered little given its strategic value.

In 1789, French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte succeeded in briefly capturing and occupying Egypt. London feared that France might one day use Egypt and then Yemen as staging posts to threaten its position in India. Egypt, which continued to maintain close relationships with France, ruled over swathes of Yemen, making this a real prospect.

Then the rise of the steamship added a second imperative. Steamships need coal. The port of Aden became crucial to fuel ships on their way through the Suez Canal and on to India.

In 1838, an Indian sailing ship, the Duria Daulat, was looted by the townspeople of Aden. Piracy was a common hobby in addition to people’s trading and agricultural activities. This provided just the pretext the British needed.

A series of skirmishes between Arabs and British troops followed and in January 1839, a force consisting of the Bombay Regiment and the 24th Regiment Bombay Native Infantry stormed the town and captured it for the loss of only 15 men. Aden was the first acquisition of Queen Victoria’s reign and would remain part of the British Empire for the next 128 years. The British extended the control of Aden by creating a buffer zone around it known as the Protectorate and they bought off the Sheikhs in the hinterland to keep open roads and maintain order.

This gave the British control of about two-thirds of Yemen’s coastline while Turkey controlled the north. Things between Turkey and the British remained stable until the First World War when troops of the 29th Indian Brigade en route through the Red Sea to Egypt were ordered to attack Turkey’s coastal forts. Their offensive failed and Turkey retaliated by attacking Aden with massive force.

First falling on the British held town of Sheikh Uthman on the fringes of Aden and famous with sailors at the time for its brothels, Turkey’s army soon reached the outskirts of Aden itself. There’s a fantastic panic telegram from the period sent by authorities in Aden to London and it reads, ‘The Turks are on the golf course.’ General George Young Husband’s relief forces from Egypt though stabilised the front line and Britain kept control of Aden, military historian Jonathan Walker has written in a fantastic colourful read, you must look at if the period interests you.

For its part, northern Yemen’s imamate gained de facto independence after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the revolution in Turkey. Imam Yahya ad-Din who ruled from 1918 until his assassination in 1948, gave London ulcers periodically. He raided British positions once in a while and during the Second World War allied with fascist Italy.

Nothing very much came of it though the British did get an opportunity once in a while to shoot at Italian aircraft over Yemen. Although London became increasingly concerned at the expensive beating of these threats, the Royal Air Force ended up providing a low-cost option by strafing tribal rebels and bombing their villages and livestock. These brutal air raids similar to those conducted at the time in India’s northwest, which we’ve discussed in past episodes of Explorer, led the Empire to be able to keep a cost-effective grip on Aden.

The birth of many Yemens

The assassination of Imam Yahya in 1948 came even as domestic opposition began to mount to his backward theocratic regime. 30 conspirators were beheaded one by one in the public square in Hajar, who his son Imam Ahmad Hamid ad-Din said were backed by Britain.

Ahmad, the great historian Fred Halliday has noted, now set about a policy of deliberate isolation, hoping to seal the imamate off from the currents of secular Arab nationalism then sweeping the Middle East. He said, ‘one must choose between being free and poor and becoming dependent and rich. I have chosen independence.’

Even as the imamate retreated inwards, Aden began a great period of post-colonial economic expansion. In 1951, British Petroleum developed a 200 acre refinery in Aden, which was staffed by British and Arab workers, but also Indians, the first to end up permanently in that country. There would be many unintended consequences of this economic boom, principal among them being a unionized workforce that was to prove itself an enormous headache for colonial administrators.

The US, meanwhile, had emerged as the preeminent global power after the Second World War and was quietly encouraging Saudi Arabia to assert its independence from London.

In 1956, following a series of skirmishes, Saudi Arabia broke off diplomatic ties altogether with the UK, ostensibly over the British invasion of the Suez Canal. The real issue was disputes over the control of oil fields on the borders of the Saudi Arabian Kingdom and Yemen. The US encouraged these tensions, seeing them as an opportunity to eventually ease the British out of the Middle East altogether.

Faced with stark economic realities and its dependence on the US, Britain began downsizing its military forces. It realized its position in Aden was increasingly untenable. And with India independent, the British had less and less reason to hang on.

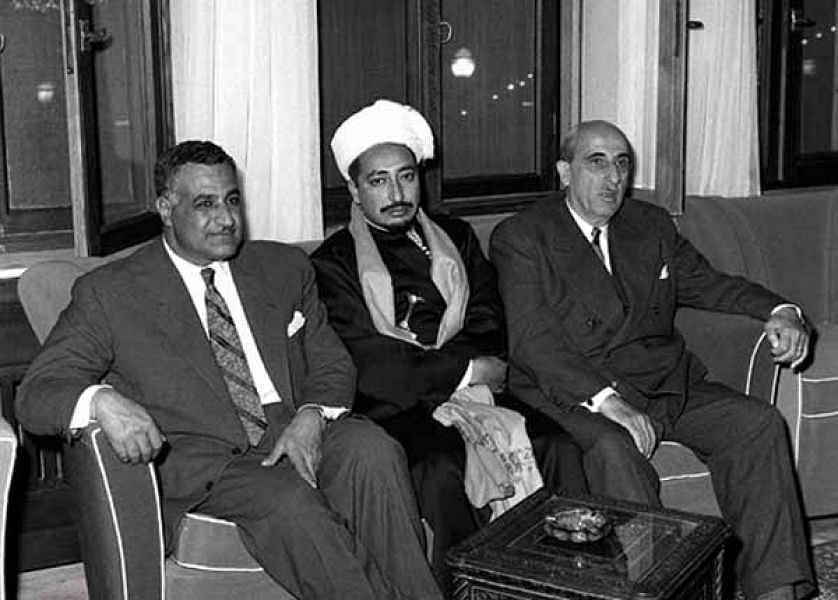

When Britain debated the future, Imam Ahmad’s successor Muhammad al-Badr turned to Egypt’s ruler Abdel Gamal Nasser in an effort to secure the imamate against Arab nationalism. In 1958, Egypt and Syria and the Kingdom of Yemen formed what was known as the United Arab Emirate. The union envisaged creating a single Arab army, foreign policy, education system and currency.

Although none of this happened, northern Yemen, the imamate region, received a flood of aid from the Soviet bloc. For its part, Britain responded by engineering an alliance of the sheikhs of southern Yemen in an effort to secure its presence after the now inevitable decolonization of south Yemen. The port of Aden had, thanks to the British Petroleum refinery, become the largest oil bunkering port in the world, handling over 5,000 ships a year.

It was also a free port, what we call today a free economic zone, with customs duty applying only on alcohol, tobacco, scents and a local narcotic, which is very popular, called khaat. The wealth of Aden was to be its undoing, however. In 1959 and 1960, large-scale industrial action or strikes by British Petroleum’s workforce paralysed the city.

The shipping business fled to the strike-free French-controlled port of Djibouti on the other side of the Red Sea. This, however, ended up creating more economic hardship in Aden, which created fertile grounds for insurrection. The federation of sheikhs created by the British, moreover, suffered from friction between its largely backward rulers and the cosmopolitan elite which controlled Aden.

Events came to a head in 1962, when Egypt-backed socialist officers finally decided to overthrow the Zaidi imamate, staging a coup and executing Imam al-Badr. There’s an interesting side story to this. Kim Philby, the MI5 double agent and KGB spy, was among the last people to meet al-Badr during a journalistic trip organised, ironically, by Saudi Arabia.

The agent’s report to his KGB handlers had not been made public, but he almost certainly came away with the impression that the last imam’s regime was tottering. Maybe that’s what led to the coup, who knows? But following the 1962 coup, insurgents in southern Yemen also declared war on Britain, demanding unification of the two parts of the country. A long and brutal counter-insurgency campaign followed, pitting an ill-funded and ill-prepared military against committed local fighters.

The British military didn’t have just insurgents to contend with. The local baboons, Walker writes, were an additional threat, biting and throwing stones at the soldiers. In one colourful case, a baboon dived into a latrine used by British marines and ‘came out covered in muck with lavatory paper all over him. He then proceeded to charge into the bivouacs, one tent after another, and he smelt to high heaven. And the heat of the day was so bad, we had to shoot him.’

The one-sided use of Royal Air Force airstrikes helped the British hang on longer than their beleaguered ground forces might have done, though sometimes at a tragic cost. The bombing of Harib in 1960, for example, created outrage across the Arab world amid reports that women and children were among the victims. The insurgency steadily gained strength and in 1967, the British finally withdrew lock, stock and barrel. Fifty corps and regiments, by the way, had served in the conflict for Britain between 62 and 67.

This was the last significant campaign waged by the British army. Fifteen British brigades were permanently disbanded after the war as an imperial army sought to make its peace with a post-imperial world.

Also Read: Why Trump’s bid to end China’s rare earth mineral monopoly may trigger a geopolitical headache

A perpetual war

There would be no peace for Yemen, though. Five years after independence, a Saudi Arabia-backed junta which ruled North Yemen went to war. The South, the only avowedly communist country in the Arab world, received the support of the Soviet bloc and a ferocious civil war followed. The two countries set aside their differences and united in 1990 after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Inside three years, though, civil war broke out again. This time, the North crushed its opponents in the South and captured Aden in 1994. Elections were held in 1999, and many observers were optimistic.

But by 2015, civil war was washing over the country yet again. Like in the past, external powers played a key role in fuelling the crisis. From the 1980s, Saudi Arabia had pushed to expand its religious influence in North Yemen, leveraging its relationship with the long-ruling military strongman Ali Abdul Saleh to send in state-backed preachers and proselytisers.

This caused a backlash among the Zaidis who were Shia and for whom the Saudi message was less than welcome. Inspired by Iran, the main ethnic Houthi clan created an armed group, Ansar Allah, and began fighting for a Zaidi theocratic state, a resurrection of the imamate that they once had. And by the way, if you’ve been wondering why you’ve heard the word Houthi so rarely since the beginning, let’s just remember Houthi is a community and Ansar Allah is the name of the political group that is being bombed.

I don’t like confusing these things because not all Houthis or all Zaidis support Ansar Allah. In 2004, Zaidi cleric Hussain Badruddin al-Houthi began an uprising against the Saleh-led government, fighting six rounds of war until 2010. Then in 2011, when the so-called Arab Spring erupted across West Asia, massive protests forced Saleh out of power.

The Gulf Cooperation Council brokered a deal between the warring parties, installing Abdu Rabbu Mansoor Hadi as president. But perhaps unsurprisingly, given the history we’ve been talking about, this peace deal did not last either. Al-Qaeda, meanwhile, cashed in on the chaos, growing dramatically in southern Yemen.

Even though President Obama waged a long-running drone war against Al-Qaeda, it proved adroit in allying with tribal factions, at one stage even exercising territorial control over towns like Mukalla. Mukalla, by the way, is part of the Hadhramaut region where Osama bin Laden’s ancestors hailed from before they moved to Saudi Arabia. Even as Al-Qaeda was slowly ground down, Iran’s Saudi proxy warfare came to centre stage.

In 2015, Saudi Arabia went directly to war in Yemen. Its generals thinking it would take six weeks to sort out the Ansarullah rebels. Thousands of bombs and tens of thousands of civilian deaths as well as a tidal wave of refugees have instead made the problem all but impossible to solve.

Ansarullah, of course, proved a much tougher nut to crack than anticipated. In 2022, using missile and drone technology supplied by Iran, it even overpowered western provided air defences to target oil refineries in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. That led the Saudis to begin a peace process which is continuing.

Even though the Saudi Arabian forces and the UAE have pulled out, efforts to hammer out a political deal aren’t easy. One option that’s being discussed is the creation of a new version of the Imamate that would concede the Houthis’ claims to autonomy in their part of the country. A Houthi state, however, would be an Iranian proxy and that would cause a real alarm in Israel.

It would also leave the question of security in the Red Sea open. This much is certain. Trump’s latest bombing is unlikely to have much of an effect on Yemen.

These bombs, after all, aren’t different from all the other bombs that have preceded them. Local people have become almost used to this level of conflict. There’s a fantastic video you can see of YouTube of a local man in a shop in Sana’a watching a bomb go off across the road from his premises and barely flinching.

In a desperately poor, dysfunctional country, perpetually perched on the edge of famine, it’s not hard for insurgents to find an endless supply of volunteers or to whip up millenarian anger among young people. Finding an actual answer to this conflict, like so many others, needs committed diplomacy and state-building efforts. And in Yemen’s tormented history, sadly, neither of these has ever been in much supply.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Train hijack by Baloch insurgents in Pakistan holds critical lesson—railways can drive geopolitics

Maybe bombing Houthis won’t end Red Sea war. But nuking sure would.

What Yemen, in general, and the Houthis, in specific, need and deserve is repeated nukings. A bunch of hydrogen bombs followed by a few atomic ones would make them understand the folly of their ways.

One can guarantee that they would sign wherever they are asked to sign and they would uphold every word of the signed agreement.

Pain is a necessary evil. The right amount of pain can make even the devil come to the negotiating table and accept terms and conditions.