In a transaction, if you’re not paying, and not being paid, you are the product. This, saying, common among cybersecurity enthusiasts, sums up perfectly why “free” online services are so much of an issue. Firefox, the browser of choice for many such enthusiasts, has now withdrawn its promise not to sell user data. Here’s why this is worrisome, and how it affects Mac users.

Firefox Abandoned its Pledge of Not Selling User Data

I first learned about this through Theo, the closest to a digital influencer the dev community has. He shared a screenshot of modifications in Mozilla’s GitHub repository, highlighting changes to the Firefox FAQ page.

If you want to see for yourself, you can check the comments on GitHub. And, for comparison’s sake, here’s the Firefox FAQ page now, and how it was a few weeks before the change. Check between the “Is Firefox safe?” and “Why is Firefox so slow?” headings. “Never say never” in its purest form.

There Are Many Browsers, But Not Many Browser Engines

Now, there is no shortage of browsers out there. If you’re comfortable with big companies hoarding data, there are Google’s Chrome and Microsoft’s Edge, just to mention a couple. But “browsers” are just part of the issue, we have to consider “browser engines” as well.

Understanding Browser Engines

An “engine” is the component of a browser responsible for displaying the pages you visit. Some parts of these pages must adhere to a set of cross-compatible elements, which are collectively called “web standards”. Mostly any browser displays these elements the same — more on that in a bit.

Other parts, however, fall out of the standards’ reach. And, for these, the engines work differently. Therefore, a website developer must decide whether to prioritize some engines or treat them all the same. Since supporting all engines equally means more work, it’s common for pages to look and behave better in more popular engines.

There’s also the issue that, even for standard elements, engines may not display things exactly the same. Firefox, e.g., is famous for its issues with color gradients. If you open the image in this Stack Overflow thread outside a browser, you’ll see what I’m talking about.

The Duopoly — Or Monopoly? — of Blink and WebKit

So, back to the previous point, which are the most popular browser engines? Apple’s WebKit and Google’s Blink — which is based on WebKit, by the way. Gecko, which powers Firefox, comes in a distant third. Other than that, there are only very niche or legacy engines.

While Blink and WebKit have significantly diverged since the fork, in 2013, they’re still very similar. That also applies to something not related to the programming: both are developed by huge tech companies. While WebKit and Blink are open source, Apple and Google, respectively, decide how to use and/or change the code.

Those who don’t want their data in the hands of such companies have, then, a single alternative: Firefox’s Gecko. There are quite a few Firefox-based browsers, to be fair. However, counting them all plus Firefox makes up for 2-4% of all internet users worldwide.

Even though this doesn’t represent much, the existence of an alternative is by itself important enough. Less competition hinders innovation, and, in this case, means tech bros get to decide how the whole internet should be.

Do You Like the Internet? Thank Firefox for it

Firefox users and Mozilla, the organization behind Firefox, have usually been the most vocal opponents of many anti-consumer changes. The very existence of Blink and WebKit wouldn’t probably be possible without Mozilla.

Firefox was created from the rubbles of Netscape Navigator, an Internet Explorer competitor in the so-called “first browser war”. IE won that war, back in the ’90s, establishing a de facto monopoly.

If it wasn’t for the creation of Firefox, all of the web nowadays would be likely directed towards Microsoft technologies. You don’t have to worship Apple to agree IE was terrible — despite it being the default Mac browser for years.

The issue was deeper than just “having another browser option”. Microsoft won the fight with Netscape because it shipped IE by default with Windows. It had 95% of the computer market share back then, so the company abused its dominant position to harm competitors. The antitrust case that followed shaped how the web, and technology in general, work nowadays. Any little freedom users have left today can be traced to that time.

Mozilla Became What It Has Sworn To Fight

This is why it’s so disheartening Mozilla broke its pledge of over two decades. Things were already bitter considering choices like repeatedly renewing the deal to use Google as the default search engine. But funding had to come from somewhere, and realistically, this choice was the lesser evil considering the possibilities.

Through the years, in fact, alternative search engines became more prominent inside Firefox, so countermeasures to Google’s monopoly somewhat existed. However, there’s not much to be done if the organization itself decides to become what it has criticized for years.

Mozilla’s decision to sell Firefox users’ data isn’t isolated. It came as part of a broader change in the organization’s terms of service, many of which are worrying.

As an example, if you use any of “Mozilla’s services” with educational content about human reproduction, you may be penalized. Firefox itself isn’t a “Mozilla service” (it’s legally a product), but Firefox Sync and Mozilla VPN are.

Therefore, sending a link of such content from one device you own to another, using Sync, is against the ToS. Watching it with the VPN on constitutes a violation as well. Now, you may not be into this kind of thing, but that’s not the point. Browsers monitoring its users’ traffic is exactly the kind of thing Mozilla was created to fight against.

There’s more to that, unfortunately. The “applicable laws or regulations” part means a whistleblower exposing corrupt corporations or governments can be ratted on as well. That’s just to mention a couple of terrible usages of such terms.

Finding Alternatives to Firefox Isn’t Hard — Unless You’re a Mac User

Okay, so why not just ditch Firefox, you ask? That’s a possibility, but there are other issues.

Ethical Concerns

Firstly, as stated previously, there’s the ethical cost of that decision. Mozilla used to be, as someone once published in Stackademic, “a revolutionary force” for internet freedom.

Leaving it behind is more than just moving to a new browser. It’s, to put it simply, giving in to people and companies that favor mass surveillance and exploiting users’ vulnerabilities.

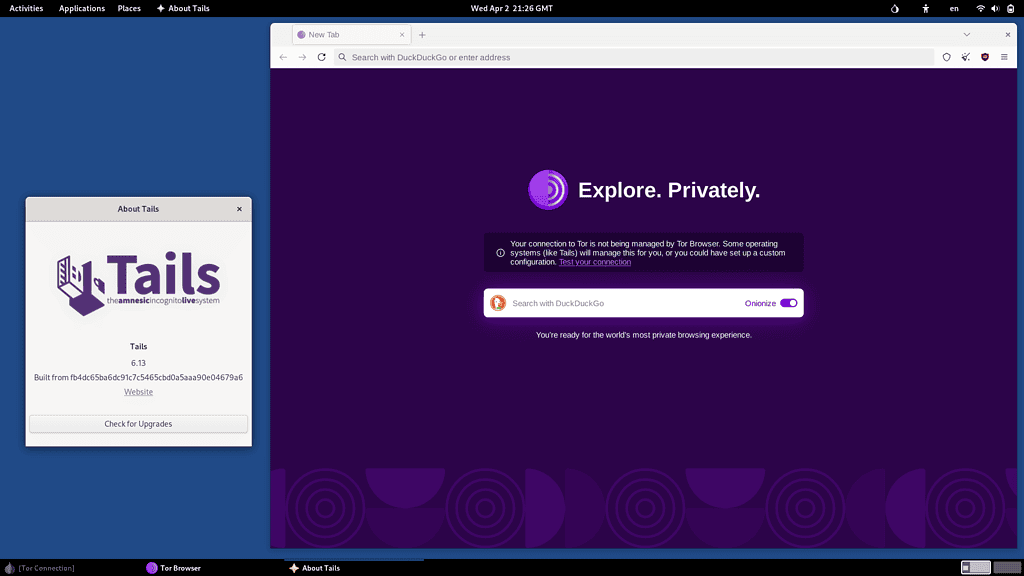

Switch Browsers? More Like Switching the Whole OS

Even if we ignore that, however, there’s the question of: move to where? Unless you go all the way down the Linux rabbit hole, there aren’t many choices out there.

Also, users have the right of not needing to switch to a whole new OS just to find a usable browser. That switch requires time (to find a suitable OS and only then move to it), and often money. Staying in macOS, I can keep using the apps I have purchased, many of which lack alternatives in other OSes.

I also have preferences about how my computer works, its user experience, design elements, and the logic behind its interface. Some of these are precisely why I went back to macOS after eight years of using multiple Linux distros.

Practical Concerns

Lastly: in macOS, there are some decent browsers, made by decent people, with decent functionalities. But that doesn’t mean much if website developers don’t support these browsers — often don’t even know they exist.

Firefox, at least, is a known name, and developers may feel compelled to optimize their pages for it. After all, the whole internet has about 5.4 billion users. Even considering the lowest market share estimate, that means Firefox has over 100 million users. You wouldn’t want your online service, on which your income depends, to be unusable by 100 million people, right?

Many of the alternative browsers, possibly most of them, use Firefox as a base. Since it remains open source, it’s quite possible to fork the code, take out the problematic parts, and compile it. While at that, a lot of developers add a few personal touches, improving on what Mozilla hasn’t so far. And that’s what causes the main issue, as stated below.

The Internet Looks Broken in Many Browsers

To mention just one example, let’s talk about LibreWolf. The developers label it “a custom version of Firefox, focused on privacy, security and freedom”, so the differences aren’t drastic. Even so, many banks simply don’t work on LibreWolf, at least with its default settings. Not that they necessarily work wonderfully on Firefox, and that’s the next point.

Mozilla made some concessions about how Firefox works, in the name of keeping the browser usable for more people. These concessions often included supporting, even if not by default, technologies that could (but not necessarily did) track users.

Even though these technologies are not part of the web standards themselves, some of them become “informal standards”. That’s simply because, for web developers, learning how to use them was easier than finding (or creating) alternatives.

If a browser’s developers decide to strongly oppose the usage of such technologies, websites will seem broken to their users. The users are not to blame, and the browser’s developers are not to blame. In a way, the websites’ developers aren’t to blame either, they simply learned what “the market” — employers and clients — required.

Why Not Just Use Safari?

That previous point is most of the reason. I know Safari has decent security features, integrates seamlessly with macOS, syncs between (Apple) devices, and is (relatively) light. As a side note on that last aspect, no Firefox user (or former user) can complain about browsers being heavy.

One thing to point out is that Apple’s devices are expensive because the company doesn’t sell your data. That’s not speculation, that’s its official policy. There are some concerns, like Google’s “default search engine” deal with Apple, similar to the one with Mozilla. But it’s up to you to accept Google’s data hoarding or not, search engines don’t change how Apple devices work.

However, there are a few points to consider that prevent me from having Safari as an alternative. Here they are.

- Safari (indirectly) strengthens user tracking: Safari’s foundation is the same as Chrome’s. Because of that, using it incentivizes developers to optimize the web for a browser known for tracking users.

- Everything in Safari, except WebKit, is closed source: I don’t think everything has to be open source. Would prefer to, but this isn’t feasible in the real world. However, open-source alternatives still exist, and I’d rather use them.

- Safari is somewhat barebones: Safari was the last of the more popular browsers to support extensions. That’s just one example. My usage is more complex than most people’s, but that doesn’t change the fact that Safari doesn’t fulfill my needs.

- Odd usability choices: Apple products require you to use them as Apple intended, not as you like. Sometimes this is acceptable, but, for Safari, the requirements are too much for me. Just as an example, displaying all pinned tabs in all windows breaks functionality for services like WhatsApp Web.

Backstabbing Users Is Never a Good Idea

Like many loyal Firefox users, my history with the browser began before it even existed. I started using Netscape Navigator around 1999, in version 4. Being about 8 at the time, I don’t remember much, but surely remember it being better than Internet Explorer.

It remained my browser of choice until about 2006 when I made the jump to Firefox — then in version 1.5. I did try some other browsers now and then, but never for ethical reasons. I simply wanted to try something new, or maybe I became interested in specific features. However, I had never disliked Firefox.

That’s why I always ended up switching back to it. Firefox always had the best balance between features I wanted, freedom of usage, performance, and compatibility with most websites.

Not this time, though. Mozilla threw out everything the foundation stood for during these almost three decades.

And it’s reaping what it sowed.

On Mozilla Connect, the foundation’s support forums, hundreds of users have been sharing their outrage since the change was announced. When its representative tried to “explain” things, using vague and elusive language, things got even worse.

Many have taken the discussion to Mozilla’s GitHub repositories, too. Some exposed their discontent on the ToS and FAQ update pull requests. Others created issues and labeled them as bugs, like “Privacy features not working“. There are also people who prefer a more direct approach, simply criticizing the foundation and calling it a day.

In any case, long-time and new users alike are furious at Mozilla. And they have every right to. Judging by how things look, one of the sole survivors of both browser wars might be in its final moments.