Dreams of Major League Baseball in Portland are periodically reawakened by promoters who name desired ballpark locations and circulate enticing illustrations. For 30 years, none have gotten to first base.

Few may know that we ever came close to cracking the major league club. But Portland was on the verge of claiming the Montreal Expos in 2001 until a “double-cross” in the state Legislature nixed financing for a stadium, deflating the deal before the public knew enough to invest their hopes.

Bud Selig, then the interim commissioner of baseball, had planned to publicly give the blessing of MLB to a future Portland team on July 7, 2001. But Steve Kanter called him that morning to call it off. The funding package had fallen apart in Salem after midnight and there would be no good news to announce.

“I had to pull the plug,” Kanter said.

Kanter, the former dean of the Lewis & Clark Law School and now a Northwest Portland resident, was president of Portland Baseball Group, a group of political insiders, business leaders, citizens, lobbyists and architects who mounted what they thought would be a six-month mission to bring big league baseball to town.

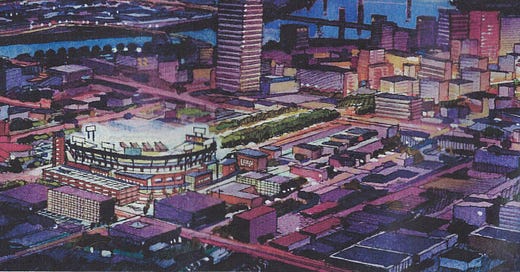

Local architect John Vosmek prepared a redesign of Civic Stadium (now Providence Park) as an interim home should the Expos be coming. Vosmek also enlisted HOK Sports of Kansas City, the preeminent designer and builder of major league baseball stadiums since the 1990s, to create a design for a permanent stadium on the site of the main U.S. Post Office on Northwest Hoyt Street, a property recently cleared for mixed-use redevelopment.

An HOK official told the group that the post office site had everything—a central city location with ample transit links surrounded by walkable neighborhoods, great views of the river and mountains—and was among the best sites for a stadium he had ever seen.

The group had the right connections but had little time to generate broad public awareness. It was to be a sprint through the legislative session to get funding, which was to be a $250 million bond program, $150 million of which would go for a stadium and the rest for public education.

A window of opportunity had opened because the Expos franchise was in free fall, bleeding about $30 million a year while losing its star players to free agency. MLB took over the team and operated it for two years while looking for a new home.

The Expos’ predicament was only one of baseball’s problems in the 1990s. A players strike had wiped out the 1994 World Series, steroids had distorted hallowed performance records, the game’s public image had tanked and leadership was in the hands of an interim commissioner, who at the same time owned the Milwaukee Brewers, a conflict of interest if ever there was one.

Kanter just happened to have made an unlikely friendship with that interim commissioner by calling him unsolicited to tell him, “I know how to fix baseball.” Surprisingly, Selig called him back, they had an “extremely candid” conversation, and before long Kanter was asked to write up his ideas as an application to become what he believed he could never be, the permanent commissioner of baseball.

Red at heart

That was actually Kanter’s second baseball dream. Growing up in Cincinnati, he hoped one day to become the shortstop for the Reds. It turned out that he was better at law and better still at talking himself into historic opportunities. Becoming the commissioner of baseball was a long shot, and he surmised that his only path would be through the power behind the throne, New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner.

Kanter pulled out all of his connections, which included a beautiful woman who was a big Yankees booster, who lined up a call with “The Boss,” Steinbrenner. Kanter, who found the man to remarkably resemble the parody of him played frequently on “Seinfeld,” remembers the call vividly.

“He pounded his fist, and I could almost feel the pounding on his desk,” Kanter said.

Steinbrenner wanted to “stop me mid-sentence so he could halt whatever it was that I was saying to tell me that I was from Ohio.

“‘Why yes, I am,’ I replied.

“He then told me he could tell anyone's birth zip code from their accent!” Kanter said.

While that was theatric, Steinbrenner could have enhanced his exceptional sensory gift with a prior scan of Kanter’s resume.

Getting down to business, Steinbrenner wanted to know what the prospective commissioner might do that could displease him.

“I would tell you no,” Kanter said, a word Steinbrenner seldom heard.

While candor was in the air, the Yankee owner handed out a bitter pill:

“Buddy just bought 29 airline tickets.”

That needed translation. Steinbrenner explained that Selig was going to visit every major league owner to sew up support for himself as permanent commissioner, and in that case, the job would be his.

Kanter’s long shot had fallen short, but he sent Selig a congratulatory message the next day and retained a friend who would one day come in handy.

Friendship renewed

Seven years later, Kanter knew the Expos problem was on Selig’s desk, and he offered a solution: move the franchise to Portland, where he was drumming up support for a local team.

Kanter had assembled a dream team of insiders who had worked at high levels in Oregon politics. They came from both sides of the aisle. Kevin Campbell was a top lobbyist who joined the team. Randy Vataha, a former NFL receiver whose business was buying and selling professional sports teams, was hired to manage the project. Sen. Mark Hatfield and former Gov. Neil Goldschmidt were backers.

Campbell said it is unlikely he would have jumped into the project if not for Kanter, whom he praised for strategic insight, credibility and “contagious enthusiasm.”

“Steve often used the phrase, ‘if done right,’” meaning it had to make sense for taxpayers and the community as well as for baseball fans.

Vataha said Kanter’s leadership was part of the reason he got him involved.

“He’s a quality guy,” he said. “We knew he wouldn’t mislead us … and it was clear he had the respect of all the local people.”

The two remain friends to this day.

The group persuaded then-Gov. John Kitzhaber to support the campaign. Twenty of 30 state senators supported a bill to allocate $150 million for a stadium in Portland.

The bill, however, was in a committee chaired by Sen. Lenn Hannon, who did not support it. Senate President Gene Derfler did not like the bill either, but he agreed to bring it to a floor vote Kitzhaber got behind it. Passage now seemed probable. But in the last hours of the 2001 session, Derfler changed his mind and shelved it after all.

An Oregonian editorial cartoon showed Derfler throwing a bean ball at a Portland baseball fan. Lawmakers told Kanter that the senate president had double-crossed him.

The Expos instead moved to Washington, D.C., in 2005, and the team became the Washington Nationals, winners of the World Series in 2019.

“We almost pulled it off,” said Vosmek, the architect.

For years, Vosmek’s office was filled with drawings and a model of the proposed ballpark, all done pro bono.

Was it the highlight of your career?

“Absolutely,” Vosmek said.

Kanter isn’t involved with the current effort to bring a major league team to Portland, though he testified in favor of enabling legislation sought by the Portland Diamond Project, which has designs for a new stadium proposed along Portland’s south waterfront. He wishes the current effort well, while noting that it will be a heavier lift than it was 25 years ago. In 2001, an existing major league team just needed a place to play, and no other cities were as well prepared as Portland. This time it would probably entail being chosen from a list of cities for an expansion franchise that could cost billions, in addition to a similar range for a stadium.

Memorabilia of the ill-fated campaign fills boxes in Kanter’s closet: a bumper sticker with an MLB logo doctored to show an umbrella in the hands of a batter, a jacket bearing the logo and unsorted documents, including the 1994 letter from the nervy fan who wrote, “I know how to fix baseball.”

Kanter sheds no tears over failing to achieve the grand prize. He has million-dollar stories to savor and recount.

“The most fun I had during this whole process was talking to George Steinbrenner,” he said. “He was just like the character on Seinfeld.”

Kanter has a new mission. He wants to talk to Mayor Keith Wilson about how to fix Portland. He strategized for months on how to get a meeting with Wilson, then ran into him in Salem when both went there to support stadium funding.

The chance encounter may or may not bear fruit, but, as his old friend Vataha affirmed, he can be very persuasive.

Allan,

Any details on the tax plan that the MLB players would be the ones paying for the stadium?