ST. PAUL — At the corner of Sixth and Cedar streets in St. Paul stood a small wooden building. Once a home for the area’s first European settlers, rain, snow and sunlight had baked the wooden panels until it looked “as if another storm will blow it away,” according to a Minneapolis Journal article published in 1888 about the opium trade.

“The only sign of life is a wreath of smoke which rises spasmodically from the chimney and the regulation yellow sign which reads: Poon Wung, Laundry,” the Minneapolis Journal reported.

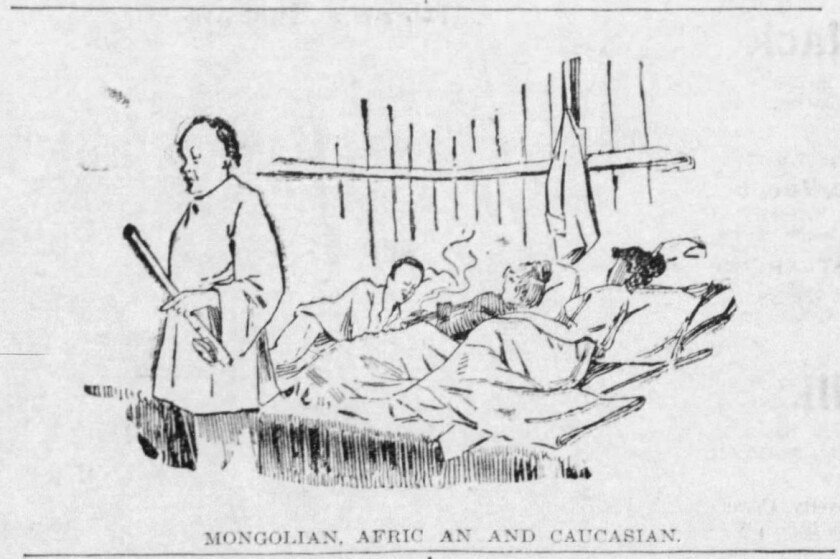

Poon Wung, a jolly man, "sleek and fat," was the owner of the laundromat, a front for a “hop hung,” or opium den. Inside the shack’s front door was an empty room, and a curtain hiding the entrance to the “heart of the joint,” where Poon sat at a small table, smoking a cigarette, and sipping tea.

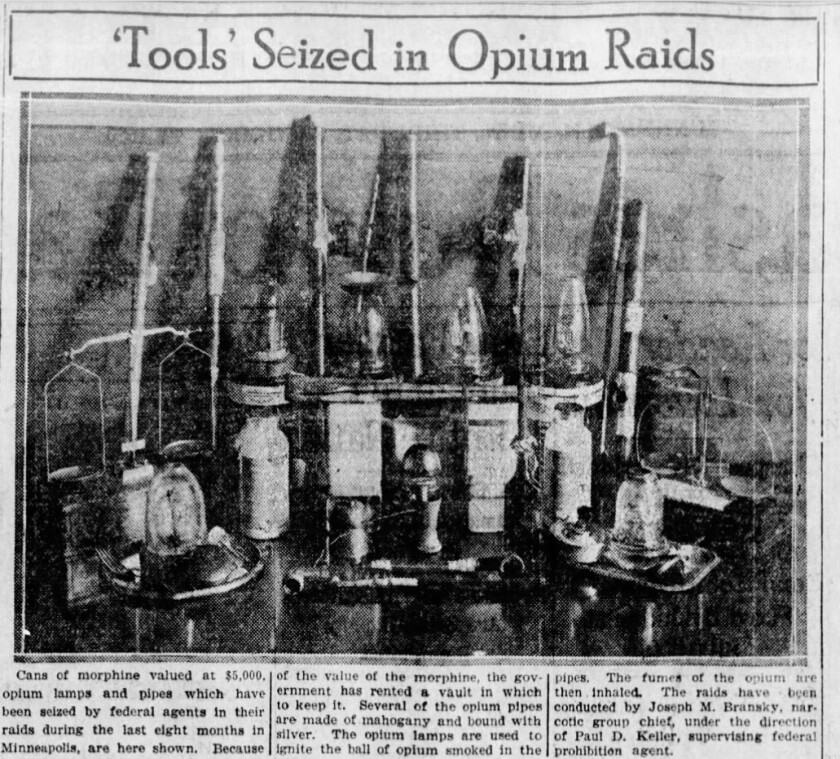

For two bits, or 25 cents, Poon used an ivory paddle to scoop thick, black paste onto a used playing card. A pipe, a tray and a metal wire were included for the den that could hold six people on clean bunk beds.

“The dim light from three little lamps over which the ‘fiends’ are cooking the drug which spits and sputters as it is turned on the wires, sending off a poisonous, sickening odor, the ghastly faces of the occupants of the bunks, intensified in the semi-darkness, and the great shadows outside the feeble circles of light, make a picture at once weird and demoniac,” the Minneapolis Journal reported.

Every month, Wung made about $25 per customer, according to the Minneapolis Journal, or about $836 in 2025 dollars.

“When Poon first settled in St. Paul he was very poor. Now he is not only rich but he ranks as one of the most influential Chinamen in the state,” the Minneapolis Journal reported, adding that his establishment was under police protection as long as he didn’t cause trouble and closed by 10 p.m. every night.

Every night, Poon’s laundry opium den filled with the poor and elite, city dwellers and pioneers.

At the time, many news reports blamed the opium epidemic on China, a country they claimed was bent on revenge for being forced to trade silks, teas and luxury goods for opium with foreign merchants.

ADVERTISEMENT

But the Chinese weren’t the only ones smuggling and selling opium in the 19th century; they became a convenient scapegoat, news articles published at the time pointed out. People from all walks of life and cultures saw profit in the illicit trade, and from 1878 to 1888, opium production in Canada destined for the United States increased from 11,000 to 102,000 pounds, according to the Oakes Times.

“Oriental vengeance,” was one headline that the Jamestown Weekly Alert published in 1890. “A civilized nation (Great Britain) compelled China to use opium. China in return has presented the world with a pipe for use in smoking the drug…” the article stated.

“Opium smoking is no longer continued to the back rooms of Chinese laundries. It has gone beyond that now, and finds its home and its white patrons in more luxurious quarters,” the Jamestown Weekly Alert reported.

Bottineau, North Dakota

At 50 years old, Archibald Curran found himself in a difficult spot shortly before Christmas in 1888. A former lake steamer captain, he was tall, sported a “heavy iron gray beard,” and had the “appearance of a man of varied experience and one who has seen much of the world,” according to the Bismarck Tribune news story published Dec. 25, 1888.

He was hoodwinked by A.E. "Leonard" Neilson, a Canadian, who showed up at his house saying he had traveled from Manitoba and his “horse was so weary that he could go no farther,” according to a statement he made to the the Bismarck Weekly Tribune.

Neilson asked Curran for help: bring multiple large wooden boxes — packed with household goods — to Bottineau and ship them to Denver for a small fee, according to the Bottineau Currant. The crates, however, were filled with nearly 400 pounds of opium, worth a total of about $11,200, the equivalent of about $374,517 today, and were confiscated in St. Paul.

ADVERTISEMENT

Curran’s name was on the paperwork, and federal agents lost no time tracking him down.

“The mysterious goings in and out on the part of Uncle Sam’s customs officers during the past week culminated in the arrest and detention of Archibald Curran…” the Bottineau Courant reported on Dec. 20, 1888.

“The smuggling case now being tried in this city is one of the most interesting in the history of the courts of the territory,” the Bismarck Tribune reported on Christmas Day 1888.

Smoking opium wasn’t technically illegal at the time, so Curran and Neilson were charged with attempting to defraud the government out of tax revenue, according to the Bottineau Courant.

“I am a victim of misfortune. I am guilty of no intentional crime or connection with that opium smuggling,” Curran told the Bismarck Weekly Tribune after his arrest.

He spent more than three months behind bars, but in March 1889, Curran was released. Neilson, however, was sentenced to seven months imprisonment.

“It is believed that the action in the case of Curran means that he will furnish evidence which will lead to the arrest of the entire gang which has been engaged in smuggling opium for years. It is undoubtedly a gigantic combination and their dishonest gains reach into the millions,” the Dickinson Press reported in March 1889.

ADVERTISEMENT

Deadwood, South Dakota

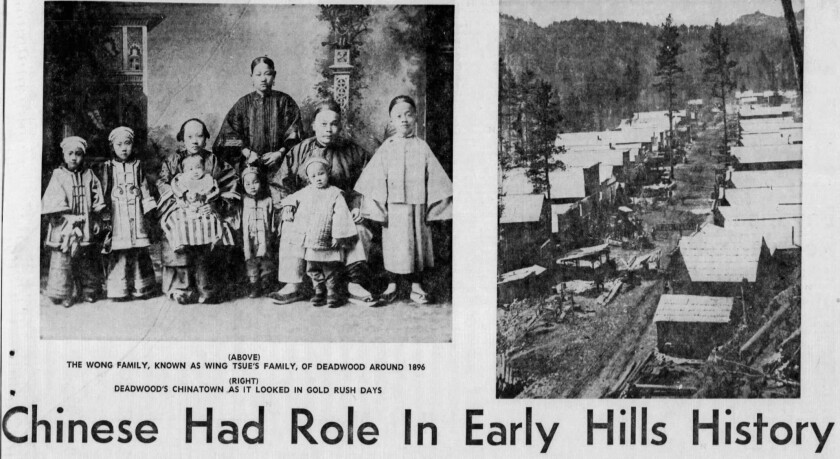

On Chinese New Year's Eve in 1885, Wing Tsue — real name Fee Lee Wong, who in 2012 was entered into the Deadwood Hall of Fame — put a large cauldron of lard on the fire. He planned to fry up Chinese doughnuts, most likely breadsticks called youtiao. He was a controversial businessman — having been arrested for owning an opium smoke house in 1880 — who owned a two-story house that doubled as a gambling joint and an opium den, a crime in Deadwood decades before opium was outlawed in the United States.

City leaders in Deadwood passed a law banning opium sales in the early 1880s, but the legislation had the opposite desired effect, according to the Bismarck Tribune.

“The city council passed a stringent ordinance against… selling opium for the purpose of smoking… which amounted to just about what all such laws and ordinances usually do. It has not decreased the smoking of opium in the slightest degree,” the Bismarck Tribune reported on June 2, 1882.

Early on Feb. 12, 1885, Wong’s pot of lard caught fire, quickly engulfing Wong’s Wing Tsue Bazaar, according to the Deadwood Daily Pioneer. A southern wind fanned the flames and before firefighters arrived at least 12 rookeries, slum-like shacks, were reduced to cinders, according to the news story.

Wong’s store was destroyed. He lost more than $800 cash he had squirreled away, while about $400 in gold in a tin box was later recovered.

“The fire accomplished what the grand jury have so far failed in doing, as it suppressed, temporarily at least the opium habit. Of the great number of opium dens that formerly graced our city, all of them have gone up in smoke with a single exception,” the news article reported.

ADVERTISEMENT

Despite the financial loss, Wong stayed. He rebuilt, but with stone instead of wood. Ten years later, his name hit the newspapers again when Deadwood police raided five Chinese opium dens, arresting 17 people from China and two white men, while confiscating eight pounds of opium and drug paraphernalia, according to the Deadwood Daily Pioneer.

Wong was one of the people arrested, but after posting $200 bail for everyone arrested, he continued his mercantile business, arguing that opium was for medicinal purposes, and never lost his reputation for being a shrewd and well-respected businessman.

The smugglers

Before opium became an illegal drug in 1909 inside the United States, the problem from a government perspective wasn’t the drug itself or the addiction that followed; it was that smugglers were avoiding $12-per-pound duties on the product, according to multiple newspaper reports.

On Feb. 9, 1909, the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act was passed, effectively banning the importation, distribution and use of opium for smoking. The laws were tightened in 1914 when the US Congress passed the Harrison Act, which taxed the production and distribution of cocaine and opiates, according to Congressional records.

The ban did nothing to stop the spread of opium, however; by 1911, opium smuggling rings in Minneapolis were “widespread,” according to the Duluth News Tribune.

Opium smuggling provided a rich opportunity for large profits. During the 1910s, one tin of opium from China cost about $2.50 to produce, and the same tin smuggled into the United States sold for more than $120, according to a news article published by the Grand Forks Herald.

ADVERTISEMENT

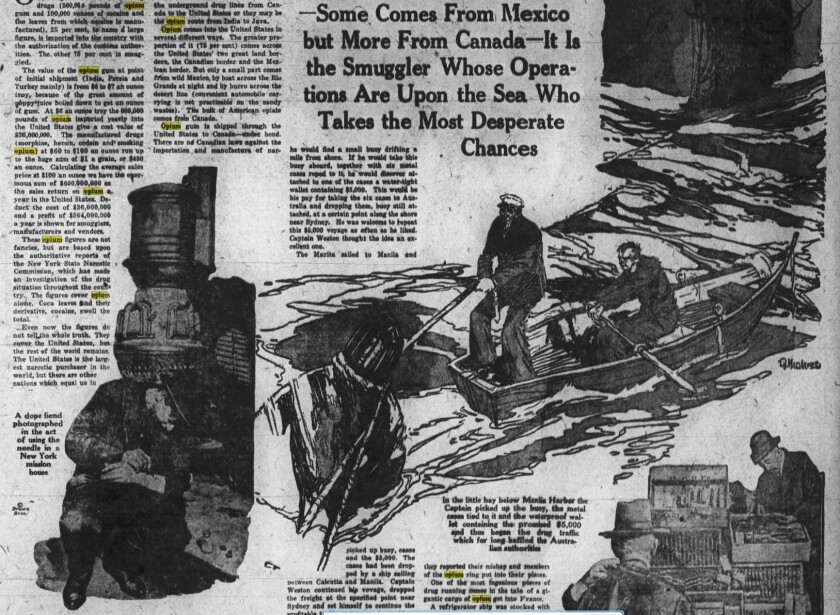

Much of the product was smuggled in from the north through Canada, south from Mexico, and west through Hawaii and then on to San Francisco where customs officials worked closely with smugglers, according to news articles in many newspapers in the 1910s. From there, the narcotic spread throughout the United States.

Smugglers used ingenious tactics to hide their narcotics, according to the Cooperstown Courier. Opium pills wrapped in oil paper were concealed inside limes; tins the size of biscuit cans were hidden in containers of salt fish. Opium tins were also tied to floating sticks to bypass customs offices.

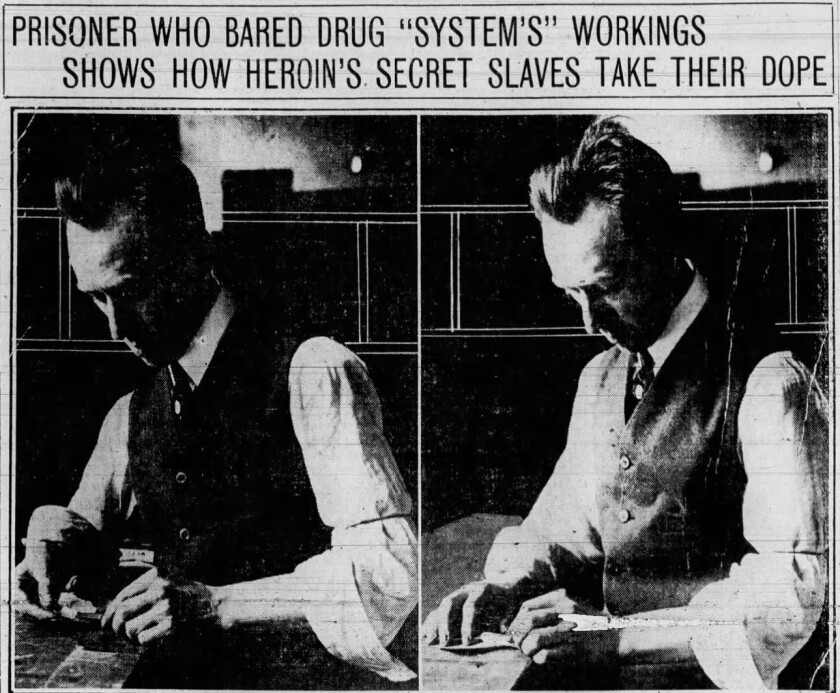

At times, opium was secreted in by sailors and then sold to railroad sleeping car porters, according to a 1911 news article in the Minneapolis Journal. Drugs were found in women’s hair, sewed into men’s hat bands, contained inside artificial limbs and automobile tires, and frequently found at the Canadian border in collars worn by dogs, according to the Austin Daily Herald in 1921.

By 1921, Americans had an “enormous annual… consumption of habit-forming drugs,” totaling more than 500,000 pounds of opium and 100,000 ounces of cocaine every year, according to a 1921 article published by the Minneapolis Journal.

‘King of the dope ring’

Police became suspicious of a Superior, Minnesota man named Frank Insco after observing him taking packages from a porter aboard a train from Canada twice a week.

Superior police then alerted federal authorities at the Internal Revenue Service, who then raided Insco’s home in 1921, according to the Duluth News Tribune.

During the raid, agents discovered thousands of dollars worth of opium and cocaine inside his house, part of which had transformed into an opium den, according to the Duluth News Tribune. Insco’s primary customers were wealthy women of high social status who “had become slaves to the drug,” and prominent men from Duluth and Superior.

Not long afterward, agents raided another opium den, the Sam Lee Laundry on Tower Avenue in Superior, and arrested Woo Ou after finding $200 worth of opium behind a secret shelf beneath a table, according to the Duluth News Tribune.

Both arrests led to the downfall of the area’s opium smuggling, and Insco, so-called “king of the dope ring,” whose drug empire stretched from eastern Canada to the Pacific Coast, according to the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Insco pleaded not guilty on eight counts of violating the Harrison anti-narcotic act, and gave a statement to the Duluth News Tribune in 1921.

“I may have been a ‘king’ for a week or two, but the kings change so rapidly that only those addicted to dope know who their master really is,” Isco told the Duluth News Tribune.

Insco was found guilty of selling drugs and was sentenced to 366 days imprisonment at United States Penitentiary Leavenworth in Kansas.