The collapse of Ruapehu Alpine Lifts has exposed a deeper tension at the heart of the maunga – who truly holds authority over its future: ski operators, the Crown or the iwi who consider it an ancestor?

More than just a ski field, Mount Ruapehu is a living tūpuna. To iwi like Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Rangi, Ngāti Hāua and others who whakapapa to the central plateau, the maunga is a sacred taonga, gifted under a tuku arrangement in 1886 – not to give it away, but to create a partnership. A partnership that, over 130 years later, still hasn’t been honoured.

Now, the maunga is at the heart of a bitter and drawn-out struggle – one involving bankruptcy, broken promises, government bailouts, Treaty breaches, and a future for the ski fields that hangs on contested ground.

So… what happened?

In 2022, Ruapehu Alpine Lifts (RAL) – the not-for-profit that had run Whakapapa and Tūroa ski fields for decades – collapsed under the weight of Covid lockdowns, poor snow seasons, ballooning debt and a $14m gondola project that never paid off. At the time, RAL owed over $40m to creditors – much of it to the Crown.

In response, the government stepped in with bailout after bailout – around $50m since 2018 – buying time to find new operators for the two ski fields. The rescue attempts were dubbed by regional development minister Shane Jones as “the last chance saloon”.

Now, both fields have been carved up and handed to new owners: Tūroa to tourism outfit Pure Tūroa, and Whakapapa to Whakapapa Holdings Ltd (WHL), a new company led by former RAL boss David Mazey.

Both were granted 10-year concessions by the Department of Conservation (DOC) to operate within Tongariro National Park – far short of the 60-year maximum term. Why? Because the deeper story is about more than just snow sports – it’s about unresolved Treaty settlements and the rangatiratanga of mana whenua.

What do local iwi think about it all?

For local iwi, Ruapehu is not just a mountain – it’s an ancestor.

That worldview is fundamental to Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Rangi, Ngāti Hāua, and Te Korowai o Te Wainuiārua. It’s why iwi have long challenged how the maunga is used – not only for environmental reasons, but because they say they were never truly part of the decision-making process.

In 1886, Horonuku Te Heuheu IV of Ngāti Tūwharetoa initiated a tuku – a conditional transfer of the mountain peaks to the Crown – with the expectation of joint guardianship. However, that vision of partnership was never realised. In 2013, the Waitangi Tribunal confirmed the tuku was misinterpreted as a “gift”.

So when the government started selling off the ski field leases, iwi were, once again, left on the sidelines.

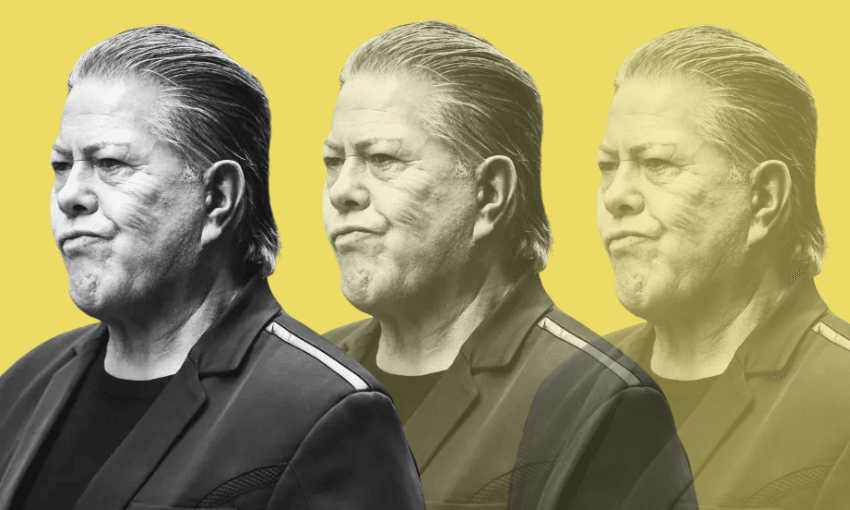

Ariki Sir Tumu Te Heuheu of Ngāti Tūwharetoa didn’t mince words in his April 2025 letter to the prime minister: “The government’s tactics of creating division between Ngāti Tūwharetoa entities as well as inappropriate disruption between us and our whanaunga iwi is unacceptable and will not be tolerated.”

He said the spirit of the tuku remained unfulfilled and he’s not alone in that critique.

Ngāti Rangi, via its trust Ngā Waihua o Paerangi, called for a rethink of ski field activity altogether, pointing to the sacredness of the Whangaehu River catchment, which begins on the maunga.

Ngāti Hāua, on the other hand, has focused on partnership and negotiated directly with local councils, striking a relationship agreement with Ruapehu District Council that emphasises a Tiriti-based, face-to-face approach to decision-making.

Where does the government sit now?

With the Crown having now exited direct involvement in operating the ski fields, iwi leaders argue that it’s walking away from its obligations – including the massive remediation bill that will fall to taxpayers if ski operations collapse again. DOC’s own books show a potential $88m liability if the maunga must be returned to its natural state. Basically, the maunga would need to be restored to its pristine condition, free of any ski infrastructure.

In effect, the Crown has offloaded the business risk – but not its moral or Treaty responsibilities.

Minister of conservation Tama Potaka has said the 10-year concessions are “short enough to allow Treaty negotiations to play out.” However, iwi want more than a delay tactic – they want actual, binding, enduring partnership in managing the maunga.

What’s next for iwi?

Well, it depends on which iwi you’re talking about.

Ngāti Tūwharetoa has signalled it will not support further development without renewed partnership talks. They are demanding direct dialogue with the prime minister. Legal counsel for the iwi has detailed multiple breaches of the Crown’s statutory and Treaty obligations to DOC, advising they will take these matters before the courts.

Ngāti Rangi continues to oppose ski operations on cultural and environmental grounds, while focusing on upholding environmental protections and kaitiakitanga.

Ngāti Hāua is pushing for greater input into concession terms and environmental safeguards. In a proactive approach, a collective of four iwi – Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Hāua, Ngāti Rangi and Te Korowai o Te Wainuiārua – had proposed taking over the management of RAL to have a more active role in the guardianship of the maunga. This reflects a desire for iwi-led management that aligns with their cultural values and responsibilities – similar to what’s been established in places like Te Urewera or Whanganui River.

What’s clear is that any long-term solution for Ruapehu must reckon with iwi rights, not just ski field economics.

And what about the skiers?

Thousands of life pass holders were left out in the cold after RAL’s liquidation. Pure Tūroa has tried to win them back with discounted season passes. Whakapapa Holdings has announced free passes for kids under 10. However, while ski businesses hustle to rebuild customer trust, the real question remains: who gets to decide the future of the maunga?

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.