On a humid Wednesday night the streets of Kabukicho, Tokyo’s most famous red light district, hum with people. Some are tourists, here to gawp and take selfies, but others are customers. Adverts for clubs flash and sing and girls dressed as maids hold signs offering deals for local bars.

In a grubby shopfront a perky cartoon featuring a cute Mr Men-style creature offers part-time work. The ad, which has an alarmingly catchy jingle, doesn’t specify what the work is, but it doesn’t need to: the answer is all around us on the brightly lit billboards advertising the charms of male and female bar hosts.

Tokyo is famous for its fairly wild red light scene. You can find anything from a handsome man to make you cry and wipe away your tears to a maid to pour your drinks and giggle at your jokes and an encounter in one of the notorious “soapland” brothels.

You can also pay to spend time with a schoolgirl. Services might include a chat over a cup of tea, a walk in the park or perhaps a photograph – with some places offering rather more intimate options.

Or at least, you can for now – unless the people inside the garish pink bus have their way.

Run by the charity Colabo since October 2018, the pink bus appears in strategically chosen spaces in the city once a week; tonight it is parked outside Shinjuku town hall. Volunteers hope to use it to provide a safe space for school-age girls at risk of being lured into the joshi kosei, or JK business, as the schoolgirl-themed services are known.

“JK business scouts tend to be men in their 20s and 30s,” says Yumeno Nito of Colabo. “They are very aware of trends and are good at knowing the girls’ economic status by looking at their clothes and makeup.” Poverty and low self-esteem are often factors in the manipulation of young girls by scouts, Nito says.

Q&AWhat is Guardian Tokyo week?

Show

As Japan's capital enters a year in the spotlight, from the Rugby World up to the 2020 Olympics, Guardian Cities is spending a week reporting live from the largest megacity on Earth. Despite being the world's riskiest place – with 37 million people vulnerable to tsunami, flooding and due a potentially catastrophic earthquake – it is also one of the most resilient, both in its hi-tech design and its pragmatic social structure. Using manga, photography, film and a group of salarimen rappers, we'll hear from the locals how they feel about their famously impenetrable city finally embracing its global crown

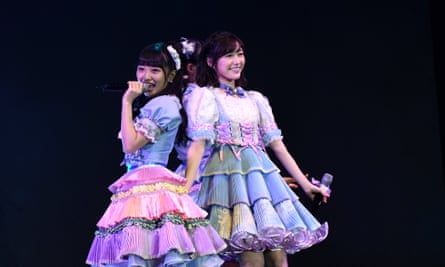

The fetishisation of Japanese schoolgirls in Japanese culture has been linked by some academics to a 1985 song called Please Don’t Take Off My School Uniform, released by the female idol group O-nyanko Club, and re-released by no less mainstream a group than AKB48, one of the highest-earning musical performers in Japan and whose single Teacher Teacher sold more than 3m copies in 2018.

The term “JK business” has become a catch-all for cafes, shops and online agencies which provide a range of “activities”, many of which are not overtly sexual. Young women in school uniforms can be offered for reflexology and massage treatments, photography sessions and “workshops” in which girls reveal glimpses of their underwear as they sit folding origami or creating jewellery.

But while many of these have a strict no-touch policy, a proportion do lead to physical encounters. And while non-physical encounters may make up the majority of reported cases of JK activity, the fact that sex does not take place does not mean no harm is done.

In 2016, Maud De Boer-Buquicchio, the UN special rapporteur on child sex trafficking and sexual abuse, raised serious concerns about Japan’s JK and pornography industry. She highlighted the lack of up-to-date official data and called for a comprehensive strategy to tackle the root causes of exploitation, noting that other forms of popular Japanese entertainment, including “junior idol culture”, are worrying examples of children being treated as sexual commodities.

“We almost allow men to say: ‘Yeah, I’m attracted to young children, as young as 14, 15,’” says Shihoko Fujiwara, founder of Lighthouse, a charity working to end human trafficking in Japan. “Even on TV, comedians will say: ‘I like to date junior high school girls.’ People make fun of those comments, but still they are made.”

Japan’s anti-prostitution laws broadly prohibit the sale and purchase of sex, but there are significant loopholes, of which establishments such as soaplands take full advantage. Crucially, in the case of JK businesses, Japan has no specific anti-trafficking laws in place. Ordinarily, a child under 18 involved in sex work is automatically considered trafficked, with harsh penalties for those responsible.

Pornography laws relating to children are also limited – they do not, for example, cover manga, anime, or virtually created content, allowing games such as 2006’s controversial (and now no longer available) RapeLay, in which the player stalks and attempts to rape a single mother and her two school-age daughters.

In 2017, with the Olympics approaching, the police cracked down on the rising number of JK businesses across Tokyo. A new ordinance requires JK businesses to be registered with the police, and prohibits the employment of girls under the age of 18. JK businesses cannot be located within 200 metres of schools, nurseries, hospitals or other public buildings, and no one under 18 can distribute fliers for the businesses, or recruit other teenagers.

Superintendent Hiroyuki Nakada, deputy manager of the Juvenile Support Division, says the police are confident that their strategy is working. But he says educating children on the dangers is also key: “It’s not enough just to control.”

Nakada says that thanks to the new, tight regulations, just three shops were prosecuted and fined last year.

“Over the past two years, since the ordinance came into force, we haven’t seen [underage] girls [in JK businessess]” says Nakada. “[Officers] have visited these shops, but they haven’t seen girls. But we think maybe there’s a loophole, maybe there are girls working, but they are probably adults who are wearing uniforms ... they call it JK business but they are probably pretending to be schoolchildren.”

Critics argue that business owners have found new ways to circumvent the law. The problem may now simply be less visible; more owners operate online, away from physical shops and cafes, and some may have simply opened new businesses under different guises.

“After the issue of JK business regulation in 2017 some shops are still operating but under a different name, such as ‘cosplay cafe’,” says Yumeno Nito of Colabo. “JK business owners are cunning and systematic.

“They are also very good at social media so they put an advert on blogs or Twitter, Line where the girls will see them. The shop opens a Twitter account and they follow girls using it.”

Fujiwara believes that the government trying to crack down on JK business may look good on the surface, but does nothing to ban other types exploitation. She also points out that more attention should be paid to buyers and to trying to change the mindset of a society that accepts commodifying children.

It was the success of Please Don’t Take off My School Uniform that some argue sparked the notorious 1990s trend for buru sera – teenage girls selling their unwashed uniforms, underwear and swimwear. From this sprang the practice of enjo kosai, or compensated dating, in which middle-aged men offered financial support to teenage girls in return for sexual relationships. This practice then became diversified and commodified into what is now know as JK business.

Nito also emphasises that the police emphasis on educating children does nothing to tackle the demand side of the JK business: “It is necessary to focus on offenders and not only on child victims. It is necessary to educate and regulate adults or offenders who buy girls a lot more than educating children.” With the Rugby World Cup and the Olympics due to happen in Tokyo in quick succession, both charities are concerned about the potential impact of thousands of curious tourists.

Another major issue is sex education in Tokyo’s schools. “There’s no sex education,” Fujiwara says baldly. “You can’t mention ‘intercourse’ or ‘sex’, but they have to somehow teach about HIV and contraception – how do you teach that without saying ‘sex’? ”

Although the police might count it a victory that some JK businesses no longer employ those under 18, Nito argues that it does not touch the root of the problem. Even if the girls offering JK services are of legal age, it contributes to a dangerous and pervasive culture of the sexualisation of minors. After all, they are pretending to be underage schoolgirls, feeding an appetite for the illicit buying of pornography and making real schoolgirls more vulnerable.

“A society that commercialises and consumes underage women as a sexually high-value commodity has a problem,” says Nito. Until that problem is addressed, Colabo’s pink bus looks set to remain a fixture under Tokyo’s red lights.

This article was amended on 17 June 2019 to more accurately reflect the views of Shihoko Fujiwara regarding the effectiveness of the crackdown on JK businesses.

Guardian Cities is live in Tokyo for a special week of in-depth reporting. Share your experiences of the city on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram using #GuardianTokyo, or via email to cities@theguardian.com